Having reread Chesterton's Orthodoxy, I can now understand why I wasn't particularly moved by it when I first read it. As I mentioned, it's anything but a systematic defense of the faith, more one man's idiosyncratic account of why he feels that Christianity is the perfect philosophy for him and for the world. But it seems to me that unless you already have a background in theology and metaphysics, you would not find his arguments particularly convincing.

As he points at in the beginning of the book, he tried -- as does any serious person -- to arrive at a comprehensive philosophy, only to realize, when he had completed it, that it already existed in the form of Christian Orthodoxy. I've pretty much had this same experience, allowing for the fact that Christianity is a rather large tent that accommodates virtually all temperaments and levels of intelligence.

This is an important coonsideration, since neither my intellect nor heart or soul could ever "find their rest" in some of the more visible forms of Christianity (which I sometimes think are a conspiracy to make Christianity look foolish). Only by first arriving at my own philosophy and then discovering -- to my surprise -- an antecedent Christian form of the more-or-less identical philosophy was I truly able to have the "ah ha" experience alluded to in a post by Walt a couple of days ago:

"The second assumption is that the Gospel has come down to us from a higher mind than ours. If there is something in it that we do not understand, the difficulty is likely to be in us and in our limitations. In attempting to make sense of the text, whenever there is any question about its intelligence, there is no doubt that the Gospel comes from a higher intelligence than ours. Where our best efforts do not yield a satisfactory sense in the Gospel, there is an opportunity for us to listen quietly with humility so that we may hear what we are not accustomed to hear."

I suppose it's similar to what so many adolescents have to go through on the road to separation and individuation -- to regard their parents as clueless idiots until they gain a little real-world experience and eventually realize how wise they were all along. The prodigal son, yada yada blah blah blah. (When I was in graduate school for my MA, I had an annoying female classmate who ended every sentence in that way [this was well before the yada yada Seinfeld episode]. I sometimes wonder how her patients fared: "Sounds like your mother never really understood you, and yada yada blah blah blah.")

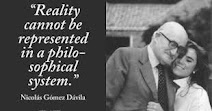

The point is, when you keep independently discovering very specific rock-bottom truths, only to learn that others have discovered the same truths, it starts to look as if either human minds are built along the same lines, or else there is an independent but invisible reality that individual minds converge upon. Obviously both must be true, since our minds are made both for and from the truth. If both of these weren't true, then there would be no way for our minds to comport themselves with any truth. In short, our minds are composed of that which they ultimately seek. Which is an example of something I thought I had discovered, only to -- here, let's pick someone at random, say, Origen:

"The apostle Paul teaches us that God's 'invisible nature' has been 'clearly perceived in the things that have been made'; He shows us that this visible world contains teaching about the invisible world, and that this earth includes certain 'images of celestial realities'.... Perhaps that is what the spokesman of the Divine Wisdom means when he expresses himself in the words: 'It is he who gave me unerring knowledge of what exists, to know the structure of the world and the unerring elements...'"

In other blah blah blah, the inside can only know the outside because the material world is an exteriorization of the same logos which interiorizes itself in the form of human consciousness. Thus, the acquisition of scientific knowledge and of truth in general is completely unproblematic in Christian metaphysics. But ask a thoughtful materialist if materialism is true, and that's the end of his materialism, since matter could never even know of truth, let alone possess it.

And it is because the world is mysteriously bifurcated into this interior and exterior, that life is (or should be, anyway) such an adventure -- adventure being the combination of strangeness and familiarity. Only human beings can be "at once astonished at the world and yet at home in it." If you are fully one or the other, you're really missing out on something vital. If you feel totally at home in the world, then you're more like an animal in the habitat it was selected to fit into. But at the same time, if you were only astonished at the world, you wouldn't be able to function in it. Psychotic people can experience each moment as a calamitous novelty, and the effect isn't pleasant surprise but nameless dread.

I would suggest that if materialism or atheism make total sense to you, it's only because you're walking around with invisible parts of yourself amputated or disfigured in some way. You're living in an environment, but it's not the human environment, which includes the invisible -- which is to say, immaterial -- worlds alluded to above.

For Chesterton, Christianity best realizes this balance of "something that is strange with something that is secure. We need to view the world as to combine an idea of wonder and an idea of welcome. We need to be happy in this wonderland without merely being comfortable." You might say that functional faith operates in the interstices of this dynamic tension between wonder and welcome, security and adventure. It is what spurs our evolution -- which could not occur if we default too far in one direction or the other, i.e., toward radical novelty or complete predictablity.

Once again, I find that jazz improvisation provides the best metaphor for this actvity, since it uses what is known -- the chordal structure of the song -- as a launching pad into the unknown, as the improviser explores the harmonic (vertical) and melodic (horizontal) potential of the chords. In fact, my book was basically an attempt at a sort of "musical performance," starting with the four chords of Matter, Life, Mind, and Spirit. Now, it would be easy enough to say that the latter three chords don't really exist, and that they're all ultimately reducible to the one and only chord of Matter. Can't play much with one chord, but at least you've solved every musical problem known to man. (By the way, you run into the same problem if you reduce the chords to pure Spirit, as do certain eastern philosophies.)

Materialism is a philosophy by the tone deaf and for the tin eared. But as I wrote in the book, if you really want to know reality in its fullness, "it is no longer adequate to be just a materialistic banjo-picker sitting barefoot on a little bridge of dogma; rather, one must have at least a nodding acquaintance with a few other instruments in order to play the cosmic suite. The universe is like a holographic, multidimensional musical score that must be read, understood, and performed. Like the score of a symphony, it can support diverse interpretations, but surely one of them cannot be 'music does not exist.'"

For each of us represents an unrepeatable melodic line that wends itself through the four great chords constituting the song of existence. Some solos are complete and musically satisfying, while others are banal, predictable, and unable to explicate the musical potential hidden in the chords.

I believe Chesterton is saying that for him, Christianity is the ideal accompaniment for this musical adventure we call "life."

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Theme Song

29 comments:

Bob, you paraphrased Origen, writing, "...the inside can only know the outside because the material world is an exteriorization of the same logos which interiorizes itself in the form of human consciousness..."

And you seemed to agree with words from my post that if we don"t get it "... the difficulty is likely to be in us and in our limitations."

Yesterday, I ran across this:

“The highest wisdom consists in this, for man to know himself, because in him God has placed his eternal word, by which all things were made and upheld...” Alipili, ‘Centrum Naturae Concentratum’

The distinction that might explain a lot is in the phrase "to know himself."

When you use the words "human consciousness," I'm betting that you mean a quality of consciousness born of self-knowledge. This is entirely different from yada yada blah blah, or "...If you feel totally at home in the world, then you're more like an animal in the habitat it was selected to fit into..."

The "invisible part amputated or disfigured" in the materialist is indeed missing: it is "self-knowledge," in a classical sense. On this, the whole matter will turn, I believe.

Or as W.S. put it in the mouth of a royal:

'If music be the food of love, play on, till I am filled.'

On locating the self worth knowing, that custodian of the eternal word, in the noise, not always a slam-dunk:

The old monks used to speak of "conquering ourselves." They spoke of this inner war of ourselves against ourselves as the most difficult and perhaps dangerous enterprises of all. It is a Platonic idea, to be sure. All disorder of the world originates in disorder of soul. If we do not learn this truth, nothing else will much matter....

-- formulation from Fr. James V. Schall citing Yves Simon

Thanks, Dilys! Good stuff!

Ah. Sometimes the spiritual war turns pessimistic. Chesterton actually writes a bit about it in The Everlasting Man.

IF Lomberg is right, we probably don't face depletion as quickly as some might suggest, but Patrick's point isn't that (of course) but that our self-insufficiency will bar us from anything and everything.

"But it seems to me that unless you already have a background in theology and metaphysics, you would not find his arguments particularly convincing."

Very true. If I had read Chesterton ten (or even five) years earlier than I did - that is, before I had studied all kinds of Eastern occultisms and esoteric monisms and found them all wanting - I would have been totally unimpressed by him. (Although I would still have loved his takedowns of modern secular philosophies - great stuff, and as you said, still amazingly relevant today, 100 years after it was written!)

"By the way, you run into the same problem if you reduce the chords to pure Spirit, as do certain eastern philosophies."

Yup. This was a major epiphany for me. After 20+ years of studying Eastern religions, I found again and again that their heart and soul - their highest, purest, most sacred teaching - is spiritual monism. Some - Alan Watts, for example - insist that it isn't monism, it's something entirely distinct and more subtle called "non-dualism". I believed this for a long time, but I'm afraid that I now know it to be bunk. At the end of the day, the highest teaching of Vedanta, of Zen, of Vajrayana, of Taoism - is monism, plain and simple. And monism is monism - it doesn't matter a whit if it's modern Western material monism or ancient Eastern spiritual monism. (If there's only One Thing, after all, terms like "material" and "spiritual" have no meaning whatsoever.) Either kind of monism lands you in the same cul-de-sac of nihilistic self-contradiction. Either kind denies, or makes nonsense of, virtually all of our everyday experience - such as our experience of free will, or of there really being such things as right and wrong, etc. As Chesterton would put it, monism has the exact quality of the madman's argument - it seems to explain everything while leaving everything out.

When I learned that Guenon's and Schuon's metaphysics were really that of monistic Vedanta (despite the fact that they were both practicing Muslims!), I began to read them with a much more critical and wary eye - and especially when they talked about Christianity. Schuon's whole doctrine of the "transcendent unity or religions", while not without a certain truth, is really just warmed-over Vedanta. In other words, to Schuon, all religions are valid, but Vedanta is ultimately more valid than the rest. Well, Christianity makes the exact same claim for itself. They might both be wrong, but they can't both be right.

I think Schuon tries to square that particular circle with the distinction between being and beyond being, but it really comes down to whether love -- which ultimately requires three -- is higher than unity.

(unity without distinction, that is)

Doesn't Chesterton say that love IS unity? I.E. Three in one? Christianity always seems to have actually a kind of zen response to monism (as odd as it is...) Monism would ask, 'is the world real or the spirit?' Christianity: Yes! And so on.

With Schuon, I mostly enjoy his intellect; his ability to take complex things and make them precise and sometimes simple. I don't agree with him about Christianity, but then, I do see a transcendent unity of religions. However, I see it as all ultimately pointing towards the same door, Christ. In that light it all makes a terrible bit of sense, even Schoun makes more sense in that light (even if he wouldn't have admitted it.)

That's how I can be a 'creedal' Christian (as Chesterton would have said) and yet read with interest the writings of monists and polytheists.

Beware, though, some Christians - they will seek to make the world as simple as the creed. It is a stupid, stupid idea. Chesterton again nailed that when he said, "If Dogma is complicated it is not because it is the Dogma itself which is complicated, but the world it must contend with." (paraphrase.)

But with the idea of life as a story, a cosmic adventure, a true tale of incredible impossibilities, the creedal Christians who are philosophical monists look very flat and wide, and not narrow in the sense in which it is most meaningful.

An example of the creedal who is a philosophical monist is the person who rejects, for instance, evolutionary science. Or, psychology. Or... etc. For them the creed becomes the 'one' thing for the mind as well... it also makes them somewhat self-unconscious.

Er, by reject I should clarify, "totally reject". There are things anyone should reject in both psychology and evolutionary science. But, babies and bathwater. Some have more baby, others more bathwater.

Yes, a body and a pile of rocks are both "unities," but one is considerably higher, for it is a dynamic unity amidst diversity.

And yes, just because there is a transcendent unity of religions, it surely doesn't mean they're all equal. If nothing else, one religion will be better able to convey that transcendent unity, which I believe Chesterton also touches on. I can't think of a positive feature from any other religion that isn't explicitly or implicitly present in Christianity.

'The "invisible part amputated or disfigured" in the materialist is indeed missing: it is "self-knowledge," in a classical sense. On this, the whole matter will turn, I believe.'

Schopenhauer would agree (from an old Gagpost):

Materialism, he says, is "the philosophy of a subject who fails to take account of himself."

By the way, are other people aware that Chesterton can be revisited in a Hal Holbrook, "Mark Twain tonight" kind of way?

"Bowdoin College Chapel, a setting that befits great thinking and lofty ideas, was the scene of a visit last Monday evening by the renowned G. K. Chesterton - or more precisely, the renowned G.K. Chesterton impersonator, John C. Chalberg."

"I think Schuon tries to square that particular circle with the distinction between being and beyond being"

If Schuon holds to this distinction, then he is really a Visishtadvaitin a la Ramanuja (or maybe a crypto-Christian), because in Advaita, any distinction between being and non-being collapses as an illusion just like every other distinction. And if he holds to this distinction, then his and Guenon's statements that Advaita is the highest metaphysical teaching are puzzling, to say the least.

Myself, I think Schuon just wants to be able to eat his cake and have it, too.

"but it really comes down to whether love -- which ultimately requires three -- is higher than unity"

Well put. That is the issue, isn't it?

"I can't think of a positive feature from any other religion that isn't explicitly or implicitly present in Christianity."

I agree. Do you know of any other religion of which this can truthfully be said?

Correction: When I said "non-being" before, I meant "beyond being". (I'm getting as bad as the New York Times....)

"I can't think of a positive feature from any other religion that isn't explicitly or implicitly present in Christianity"

Finding one would be somewhat complicated by defining "positive features" as "features in line with your own value set".

I remain somewhat perplexed by Bob's earlier assertion that Christianity only gradually Christianized Western man (in response to questions on slavery in the Bible). The suggestion would be that present Christians are better Christians than previous ones. If this is true, then future Christians might be better still -- but what would their values be? What are the future values that will be found to be "implicit" in Christian gospel?

CL, Christianity is like the Car to the Carriage; it did not make (for instance) slavery illegal or impossible, but rather made a world where it was possible not to have slaves. And in being better, it eventually created (or will create) a world in which there are no slaves.

Likewise, the Car did not make the Carriage illegal or impossible, but rather made possible a world without Carriages. And in being better it eventually made them obsolete.

Warren said,

"When I learned that Guenon's and Schuon's metaphysics were really that of monistic Vedanta (despite the fact that they were both practicing Muslims!), I began to read them with a much more critical and wary eye - and especially when they talked about Christianity. Schuon's whole doctrine of the "transcendent unity or religions", while not without a certain truth, is really just warmed-over Vedanta. In other words, to Schuon, all religions are valid, but Vedanta is ultimately more valid than the rest. Well, Christianity makes the exact same claim for itself. They might both be wrong, but they can't both be right."

I suggest that both Schuon and Guenon are simply beyond you Warren, and therefore, not meant for your consumption. Further, I simply cannot help but notice, over and over again, that once one becomes a "formed" (practically and psychologically) Christian, the idea of a real transcendent unity simply fades away. The only way it can be understood is how River views it--"all ultimately pointing towards the same door, Christs." I really only know of Cutsinger who escapes this phenomenon.

As for the idea that only Christianity contains all the positive features of the other religions, I could not agree more. Conversely, all the other religions do too.

Joseph, I think you may misunderstand me. If you wish, Christ is simply the embodiment, or incarnation of the nonlocal Telos. Thus when I say people ultimately come to him it is that in the end they assent in some form to the truth of this nonlocal Telos and it has all of the characteristics of the Son. They may never call their nonlocal Telos 'The Son of God' or even identify it with 'Jesus Christ of Nazareth' but nontheless having known him I know it to be so. And in their perception, perhaps I have assented to the important point of their own religious tradition. I don't know.

It also seems odd that we would assume the world is basically the same as it was before he came.

But, I may misunderstand you as much as you, I.

River,

Many thanks for you fine and beautiful clarification. I stand corrected, certainly.

Though I don't understand why you say this, "It also seems odd that we would assume the world is basically the same as it was before he came", I would never make those assumptions.

Ah, I don't know. I guess I was right about the misunderstanding, then? I was always great at significant figures and estimated error.

The reason for the insistence on Christ's specific name and nature is that.. well... in the words of my generation: It's the awesomest thing evar. So I hope it comes across as an expression of the joy of the 'Heavenly Treasure' and not of the hissing anger of the inquisitor.

"I suggest that both Schuon and Guenon are simply beyond you Warren, and therefore, not meant for your consumption."

Ditto for Christianity and you, Joseph. Except that, even though beyond you, it is still meant for your consumption (most literally).

Music and song has been used in many creative ways. It can also be a wonderful way of getting a message out or connecting to God. It can be a political or a spiritual message. I just saw a website about Estonia’s Singing Revolution – http://singingrevolution.com; this is quite inspirational. People came together to revolt against Russia using song.

Warren,

I could not agree more, as all religion is beyond me, including Christianity.

I hope that I may be led by that Christ that River speaks of to continue to know and love, however.

I was rather more interested in the other part of my question, River -- is Christianity still developing, and what will be Christian values in the future?

cl: To figure it out, you'd have to take an adventure inside Christianity. Suffice it to say until Athanasius' archetype shows up again, we won't know for sure.

(This is to say, the values are implicit in my view and become explicated over time.)

Post a Comment