Douthat's Bad Religion: How We Became a Nation of Heretics very much dovetails with our recent posts on the subject of meta-theology. It too raises many more problems than it resolves. Moreover, the book is more sociological than theological, such that the author never even gets around to defining exactly what he means by heresy or bad religion. Rather, he just knows them when he sees them. But by what criteria?

Schuon, who is deeper and more subtle than any mere Timesman could ever be, notes that there are two forms of heresy, intrinsic and extrinsic. The latter applies only to this or that religion, while the former goes to religion as such.

For example, it would represent a Christian heresy to regard Mary as co-redemptrix. But is belief in salvation via the divine feminine intrinsically heretical?

Actually, it looks like the idea is only borderline heretical, at least for Catholics; or, it can be kosher so long as Mary isn't on the identical plane as Jesus. But for Protestants the whole idea would indeed be heretical. This only goes to the difficulty of nailing down heresy, both intrinsic and extrinsic.

Also, I have this idea that when a religion declares a cosmic orthodoxy to be heretical, the rejected truth will have a way of returning unbidden and unnoticed. The question of Mary is just one example: you can drive the divine feminine out with a pitchfork, but she always returns.

Furthermore -- and more problematically -- she can return in distorted, grotesque, and deviant ways, as in feminism, Gaia-ism, and the cult of global warming. It is very much as if the Church's focus on Mary allows for a healthy expression of a kind of intrinsic longing, for on the human plane it can't get any more primordial than the mamamatrix. It's gonna come out somehow.

The rock bottom question is how to determine when religion is bad and/or heretical. Again, by what criteria? By what right can a man who believes in the resurrection criticize the man who believes in reincarnation? Surely, he can't just call him irrational, let alone heretical, since reincarnation would be a Christian heresy but Hindu orthodoxy.

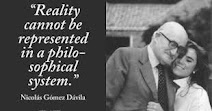

In a way, Schuon's entire oeuvre deals with this question from one angle or another "Exoterism," he writes, "puts the form -- the credo -- above the essence -- Universal Truth," while esoterism (or what we are calling meta-theology) regards the form (credo) as a function of the essence (Universal Truth). A deviation from this Universal Truth would represent an intrinsic heresy.

Let's take an obvious Universal Truth, that God is one. A religion that posits, say, two ultimate realities in eternal conflict would be intrinsically heretical. Even -- or especially -- the early fathers had to grapple with this one: how to reconcile God's threeness with his oneness without descending into intrinsic heresy.

Those early ecumenical councils testify to just how seriously they took the matter. Indeed, if the second commandment conveys an intrinsic orthodoxy -- don't worship idols and other false gods -- then everything was on the line in getting it right. Get it wrong and you end up with an intrinsically heretical religion such as Scientology or leftism.

In short, on the one hand they were obviously dealing with questions of extrinsic heresy, i.e., heresies unique to Christianity. But without stating it or even realizing it, they were also dealing with questions of intrinsic heresy, i.e., ruling out metaphysical ideas that are just plain wrong, everywhere and everywhen.

The question is, is the credo -- the particular form -- the criterion of the Universal Truth, or is there a Universal Truth that is the criterion of the particular form? It seems to me that asking this approaches a kind of vertical third-rail. Within a religion, one is discouraged from touching it.

Why is this? Because doing so might relativize the credo, such that it is no longer possible to believe it in good faith. Religions tend to absolutize themselves because failure to do so will result in failure to express and transmit absoluteness, at least to the average Joe.

Just thinking out loud here, but what if we cannot actually separate the form from the essence? This was the big divide between Plato and Aristotle -- that and the question of boxers vs. briefs -- i.e., whether the essence is in the form, or whether there is a "platonic" realm of pure essences above the individual expression. But it's not a crude either/or question, hence the breakthrough discovery of the boxer brief.

Seriously: what if there is no essence except in its expression? In our minds we can divide them, but they are really indivisible -- just as we can recognize a frog, but there is no nonlocal realm of frogginess that exists separately from the Frenchman in question.

"What characterizes esoterism" writes Schuon, is that "on contact with a dogmatic system, it universalizes the symbol or the religious concept..."

10 comments:

Maybe this explains why some exoteric dogmatic types are so uptight: those briefs are just too snug! Not to mention the esoteric unhinged types can be a tad flightly: those boxers just don't secure things well enough.

Furthermore -- and more problematically -- she can return in distorted, grotesque, and deviant ways, as in feminism, Gaia-ism, and the cult of global warming.

There was a review recently of the new Wonder Woman movie where some woman in the audience was weeping with joy that finally a woman was depicted as savior of the world. Mary may not have charged out and punched Nazis or AGW deniers (or whatever Wonder Woman is up to these days), but in her self-giving Yes she welcomed her role as the mother of God - humble, and feminine in the very best sense of the word. In righting the wrong of Eve, she did indeed play a part in saving the world.

Re. how to determine what constitutes universal heresy, as the man said: "By their fruits, nuts and flakes you shall know them." In other words, the essence is in the expression. Bad religion bears bad fruit, as any place being invaded by sharia-enforcing Muslims or antifa goons can attest.

Ted you've nailed it: how do we combine the support of tradition with the freedom of a Subgenius?

Well, if Space gets formless and void, and Time is of the essence, turn on the Light.

Space gets shiny, Time becomes faded. The price has been paid.

We’re all heretics in the light of truth, no doubt. Schuon was certainly an extrinsic heretic, both in Christian and Islamic terms. And his reduction of God to the ‘relatively absolute’ is an intrinsic heresy caused by his error in placing advaita Vedanta at the top of the metaphysical pile, itself caused, I would say, by him prioritising the knowledge of mind over the knowledge of love.

"...such that the author never even gets around to defining exactly what he means by heresy or bad religion. Rather, he just knows them when he sees them. But by what criteria?"

Not really religion (except to him) but Hemingway treated "what is true" like this. He would always refer to what was true or what wasn't but tried to write that way which I suppose was a way of proving it. Anyway, it seems the definition might not be the interesting part, but developing a sense for "it" is; which is a kind of discernment, I think. The closest thing to a criteria he used was whether a character would do something or not.

A little like prayer. It can't be completely defined (thanks goodness) except sufficiently, or cataloged in to types, and by it's fruit.

Yes, it's a more mysterious process than merely "having" or "knowing" truth. More like being in, coming from, or moving toward the truth. Philosophy is about the loving, not the having.

It also reminds me of what Jaki says about words: they are like clouds, in that from a distance they look rather solid and bounded. But move closer, and the boundary loses its sharpness, and one is surrounded by fog and mist. Nevertheless, a word is a word. Kind of like wave-particle: a word is a quintessential wavicle. Probably the Word is too....

"Seriously: what if there is no essence except in its expression? In our minds we can divide them, but they are really indivisible -- just as we can recognize a frog, but there is no nonlocal realm of frogginess that exists separately from the Frenchman in question."

All seriousness begins with what seriously cannot be... because that is the perfect starting point. Like a point, for instance. Euclid had the oh so helpful definition, of it '... having no width, length, or breadth, but as an indivisible location.' Such a thing cannot be, and literalists have spazed out over that, for millennia, whereas those with imagination 'got' it right off. The definition cannot possibly Be, but it enables us to imagine more than anyone could ever imagine. Same with a line, "...A line is a breadthless length whose extremities are points." Again, never was, and never could be, but it is it's impossibility that enables all that can be imagined, to be imagined. IOW, the Impossibly stark Intrinsic, and Extrinsic, enable the Essential to be. And of course, for the Hat - Trick, picture any one of the three, without the others, and eternity is at hand....

Post a Comment