As I've mentioned before, I'm not a bitter person, but I do still mildly resent the fact that it took me half my life to unlearn my left wing brain-washing and soul-dirtying and rearrive at where my philosophical endeavors should have started to begin with. I wasted so much time assimilating things that are not only wrong but harmful to the soul and incompatible with true happiness or fulfillment.

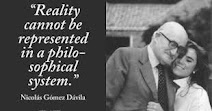

What in the world is the world? Or, to put it another way, what kind of world is the world of man, and is it the same as the world? Ever since Kant, the answer has been No: our world -- the world we perceive -- is just a form of our sensibility, a kind of projection of our neurology. Therefore, it is not the world. Rather, the world -- whatever that is -- is radically inaccessible to man. (Which begs the question of how we can even posit it, but whatever.)

This question is addressed in an enjoyable book I'm currently reading, For Love of Wisdom: Essays on the Nature of Philosophy, by Josef Pieper. One of the themes Pieper develops is the idea that all other animals merely live in a world, whereas human beings are privileged to (potentially, at least) live in the world.

For example, people assume that all animals with eyes, when they look at an object, see the same thing, when this is demonstrably untrue.

Pieper cites the example of a certain bird that preys on grasshoppers but is incapable of seeing the grasshopper if it isn't moving. Only in leaping does the grasshopper become distinct from the background -- which is why many insects (and higher animals) "play dead."

In their resting form, it is not so much that they are dead as literally invisible. It is as if they drop into a hole and no longer exist in the world of the predator. Even if the bird were starving, it could search and search, and yet, never find the unmoving grasshopper right under its beak.

What this means is that the animal cannot transcend its biological boundaries, even with an organ -- the eye -- seemingly equipped for the task.

Pieper quotes the biologist Uexküll, who draws a distinction between the animal's environment and the actual world. As he writes, "The environments of animals are comparable in no way to open nature, but rather to a cramped, ill-furnished apartment."

Animals are confined to the environment to which they are adapted, and from which they can never escape. Most of the world is simply not perceived or even capable of being perceived. In fact, the world did not come into view until human beings happened upon the scene.

But given Darwinian principles -- which, by the way, we can only know about because we have transcended them -- how did mankind escape its cramped environment and enter the wider world?

Or did we? Are we as trapped in a narrow cross-section of reality as our tenured apes? If so, then both science and religion are impossible. Like the bird looking for the immobile grasshopper, we could find neither "the world" nor "God," despite the most diligent searching. Indeed, we wouldn't even know of the existence of the reality for which to search. But if science is possible, then God is necessary. Or, to put it another way, since God exists, science is possible.

Pieper writes that the human spirit is not so much defined by the property of immateriality as it is "by the ability to enter into relations with Being as a totality," in a way that transcends our mere animal-environmental boundaries.

Now, as Schuon always emphasized, the intellect is not restricted to a particular environment. Rather, it is universal -- "relatively absolute" -- and therefore able to know the world. As Pieper writes, "it belongs to the very nature of a spiritual being to rise above the environment and so transcend adaptation and confinement," which in turn explains "the at once liberating and imperiling character with which the nature of spirit is immediately associated."

This is what I was driving at on p. 92 of the book: "Up to the threshold of the third singularity, biology was firmly in control of the hominids, and for most of evolution, mind (such as it was) existed to serve the needs of the primate body. Natural selection did not, and could not have, 'programmed' us to know reality, only to survive in a narrow 'reality tunnel' constructed within the dialectical space between the world and our evolved senses."

But then suddenly Darwin was cast aside and "mind crossed a boundary into a realm wholly its own, a multidimensional landscape unmappable by science and unexplainable by natural selection"; humans ventured out of biological necessity and "into a realm with a vastly greater degree of freedom, well beyond the confining prison walls of the senses."

Thus, natural selection is adequate to explain adaptation to an environment, but it cannot explain our discovery and comprehension of the world. Pieper quotes Aristotle, who wrote that "the soul is in a way all existing things."

What does he mean by this? What he means is that the soul is able to put itself in relation to the totality of Being. While other animals have only their little slice of Being, the human is able to encounter Being as a whole.

Thus -- running out of time here, but thus -- to be in Spirit is "to exist amid reality as a whole, in the face of the totality of Being." Spirit is not a world, but the world. Or, to be precise, "spirit" and "world" are reciprocal concepts, the one being impossible in the absence of the other. Science itself is a spiritual world, or it is no world at all, only an environment. Usually an academic environment.

Bottom line: there is no naturalistic way to get from the restricted intelligence of animals to the open intelligence of humans.

19 comments:

"suddenly Darwin was cast aside"

Well. Is the historical development of the neocortex and its ensuing natural selection susceptible to study?

I have no problem with its gradual development and with rationality as a spectrum of abilities.

The big non-material moment is the dawn not just of self-consciousness, but as a Self in relation to other Selves. "OMG, Cavegirl, you ... you CAVEGIRL! Me CAVEMAN! We CAVE ... (pointing) we CAVEPEOPLE!"

Has anyone tried to write, say, a Dialogues of the Neolithic?

Interesting that this post survived after all that seven year selecting.

Plus, I was having a similar dream this morning -- about the differences between man and our best friend. The dream is distilling down to man seeing the difference between love and sex and that on the other paw the dog only sees sex. Or only sees food. And that I think food to him is actually a higher desire than sex and would drop the latter for the former if a steak were thrown in the mix. And that love is the highest desire with man (or should be). Unfortunately, our culture is conflating love and sex. As in, love is expressed as sex no matter the boundary. This is akin to seeing only sex or it having the highest value.

In their resting form, it is not so much that they are dead as literally invisible.

I have that problem with stuff in the fridge and around the kitchen.

The more we learn and the more we look at natural selection and adaptation and genetics, sometimes it sure looks like the potential is there waiting for the trigger.

To play off Magister's example, you may need a neocortex to be fully human so "humanness" has to wait until the biological structure develops to express itself.

The spirit is willing but the flesh is the weak link.

Life makes a lot more sense if the spirit precedes.

Animals are confined to the environment to which they are adapted, and from which they can never escape.

And how many people live their lives in just the same way? Though most do try to escape, one way or another. Usually the wrong way.

Rick, re. love and sex, it seems like people either completely divorce the two, so that they really are just doing like they do on the Discovery channel (heh - I bet the Bloodhound Gang never imagined that Discovery would eventually veer away from documentaries about wild animals and fixate on documentaries about wild humans instead...) or merge them in ways they were never meant to be merged, as in the Esolen article from Friday.

Yes, John, or the tool shed. I'd swear sometimes wrenches evolved legs and sneaked out.

Or was that the wenches?

Rick said: This is akin to seeing only sex or it having the highest value.

Except that the grasshopper the bird sees is actually food. Most of the so-called "sex" that we're constantly bombarded with would be better referred to as onanistic consumerism. I am beginning to think that relatively few people in our culture actually have sex...

"Pieper writes that the human spirit is not so much defined by the property of immateriality as it is "by the ability to enter into relations with Being as a totality," in a way that transcends our mere animal-environmental boundaries.

Now, as Schuon always emphasized, the intellect is not restricted to a particular environment. Rather, it is universal -- "relatively absolute" -- and therefore able to know the world. As Pieper writes, "it belongs to the very nature of a spiritual being to rise above the environment and so transcend adaptation and confinement," which in turn explains "the at once liberating and imperiling character with which the nature of spirit is immediately associated."

"For Love of Wisdom" is one of my favorite Pieper collections, and that essay in particular, for the way it stands 'popular wisdom' on its head and puts your roots to the sky.

How mired in the mud, and muddied to appear deep, it shows kantian modernity to be. Of course the tenured simply play dead and hope you won't see them... and those educated by them won't... but there are other predators about, and they simply adjust their bandit masks, rub their opposables and toss 'em about for play.

humans ventured out of biological necessity and "into a realm with a vastly greater degree of freedom, well beyond the confining prison walls of the senses."

One can't help getting the impression that we have been adapted to an environment other than the one we currently occupy...

(sorry, thoughts coming piecemeal as I work through some buggy code)

...and yet, we are embodied creatures. We are each our own little mystery incarnate, running around somehow both in and partaking of this world and yet obviously not of it...

No wonder we are promised new bodies.

Paul said.. "Most of the so-called "sex" that we're constantly bombarded with would be better referred to as onanistic consumerism."

If ordinary words are good enough for Jesus...

Rick, I did not mean that as a detraction from what you were saying, and my apologies if that is what was conveyed. I only mean that what our culture promises is decidedly NOT what is actually delivered. Our culture is so confused, we don't even know what sex is any more.

I don't know why that particular lie has been irking me so much of late, I feel like my aggravation with it has been stewing in my comments quite a bit lately. It is difficult to see my generation and the one that has followed so completely confused on the matter. It angers me that our culture actively encourages children to mutilate their bodies and embrace their disorder in the name of "sexual freedom", which will not even be waiting for them at the end of the day. And all in the name of making a buck or winning a vote. Feh.

Paul, I think we get where you're coming from. I've often had the thought that the most subversive sex anyone can have these days is within the bounds of marriage, and "vanilla."

***

Apropos last week's discussions, there's a great article (and links) at American Thinker about being raised by gay parents. Apparently, it's not quite as awesome as the LGBT community would have us believe, but to say anything is to be a h8ter.

Paul, no worries. We're on the same page.

Julie, that AT article. It reminds of that joke Mushroom told here once (I think it was Mush) that goes something like, throw a rock into a bushel of pigs and the one that squeals is the one you hit.

You know it's been a while when you get turned on by the word "vanilla".

Paul said "I only mean that what our culture promises is decidedly NOT what is actually delivered."

That's a common refrain, believe me. In Modernity everything is reduced, taken down from the highest abstraction, to the lowest perceivable perception or stimulation. From reducing parenting to spending 'quality time', to citizenship being reduced to simply being documented; from marriage to being issued marriage licenses, and Individual Rights being reduced to (and replaced by) paid perks, acceptable forms of speech and inoffensive weapons for self-defense.

It's the anti-hierarchical, anti-conceptual and ultimately anti-reality nature of the left. It 'began' in earnest in the modern era with Descartes' Cogito and method of doubt, and with every new attempt at (and acceptance of) replacing what Is with what they wish it were, we will continue to fall at an ever increasing rate of speed.

The good news is, if not pulled up, we'll never hit bottom. The bad news is, there is no bottom.

And the Lord said, [...] this they begin to do: and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do.

Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another's speech.

I think it is easy to misunderstand the mercy of God's actions in the story of Babel. We easily misinterpret it as a story about God's offended sensibilities, when in reality it is an enormous, undeserved grace that He confounds the work of man. We are constantly seeing the product of the unrestrained implementation of what man imagines for himself to do.

Post a Comment